Click here for a full report on the Tweets from the #THATCampHP hashtag.

Some quick data:

823 Tweets from 94 Contributors.

448,739 Impressions.

Top Tweeters2c2b2b;">:

@allistelling: 117

@esquetee: 109

Most Mentioned:

@audreywatters: 91

Click here for a full report on the Tweets from the #THATCampHP hashtag.

Some quick data:

823 Tweets from 94 Contributors.

448,739 Impressions.

Top Tweeters2c2b2b;">:

@allistelling: 117

@esquetee: 109

Most Mentioned:

@audreywatters: 91

At some point on Sunday, November 4, tweet on the #thatcamphp hashtag about something you’ve done since THATCamp Hybrid Pedagogy that used or engaged or built upon what you learned here. Let’s also organize Google hangouts, blogging carnivals, and other forms of interaction designed to draw us back together and into conversation.

Digi the Duck made an appearance this morning at THATCampHP. The good-humored duck said he was hoping to use some of the energy from Audrey Watters‘s excellent talk on publishing outside the academy to promote DigiWriMo — Digital Writing Month.

Modeled after the inspirational National Novel Writing Month (NaNoWriMo), DigiWriMo encourages ambitious writers to create 50,000 words of digital writing in the thirty days of November. DigiWriMo’s participants will conspire, collaborate, co-author, cooperate, collude, and even compete to reach their goal in whatever form they see fit: blog posts, text message novellas, code poems, Twitter poems, wiki novels, some creative wizardry of text and image, and more! Digi and the DigiWriMo team encourage all the creative minds who will be too busy to reach 50,000 words to concoct their own goals.

Digi says he hopes you’ll encourage your students, fellow faculty, friends, neighbors, dog-walker, and others to join DigiWriMo this November. To pre-register, visit www.DigiWriMo.com.

A lot of wonderful conversations are sprouting up both in sessions, at lunch, and in passing. And along with that, a lot of great photos are being posted. Below, you will find a bunch of pictures I am attempting to collect off of twitter so you can access them in one easy location. Enjoy!

Schedule Collaborated and Made – Photo by @rogerwhitson

Photo by @esquetee

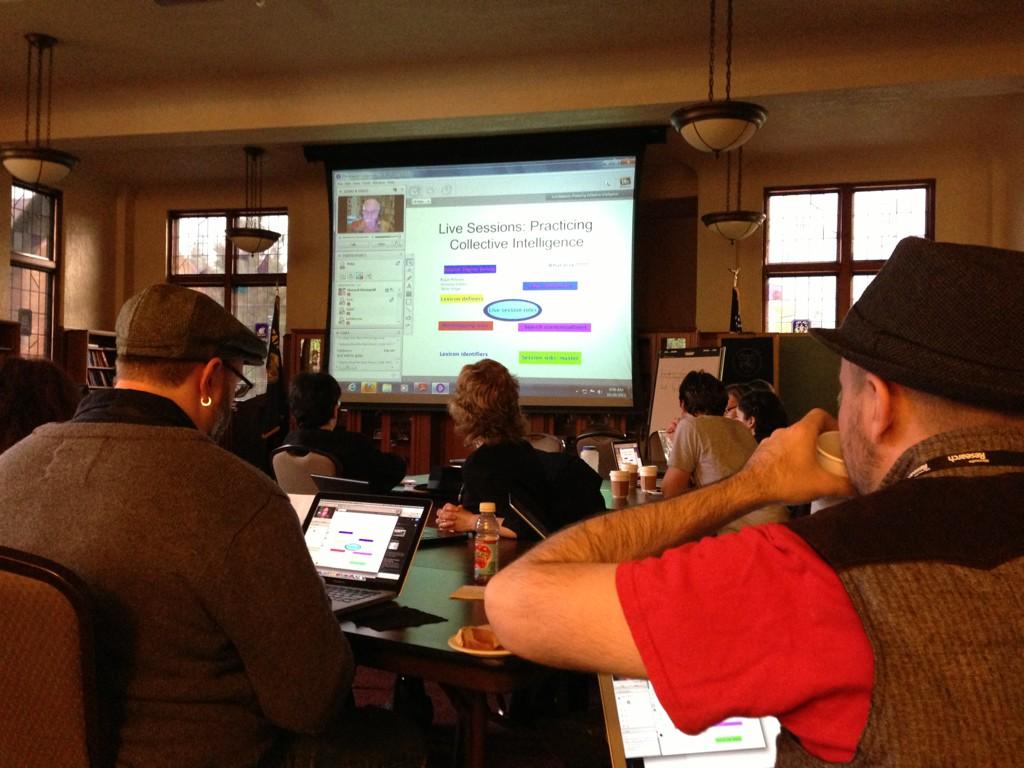

Howard Rheingold gives an interactive talk. Photo by @erikpalmer

Participants in a session all join Hangout together. Photo by @erikpalmer

Rheingold’s talk from another angle. Drink that coffee, Roger! Photo by @kathiiberens

THATcampHP from a different angle. Photo by @andycampbell

THATcampHP Google Hangout and Jesse’s face – Photo by @ldhunter

In case you were thinking about food – here’s THATcampHP lunch! Photo by @vrobin1000

All roads lead to THATcamp – well… and Guitar. Photo by @allistelling

Another angle on Lunch, and scheduling it out – photo by @allistelling

Hanging out with Jesse – Photo by @erikpalmer

THATCamp un-conferences are about redesigning how scholarly and critical conversations work. If you’ve never been to a THATCamp before, here are some short reminders for un-conferencing this weekend. For a more, see Tom Scheinfeldt’s THATCamp Groundrules. See also THATCamp LAC’s More Hack Guide, compiled earlier this year.

The Rule of Two Feet: Use them. You’re not beholden to any particular session. Feel free to get up, move around, browse, and engage where and when you’d like. Use the Twitter hashtag (#thatcamphp) to follow what’s going on in other rooms.

Less Yack More Hack: Make something, write something, plan something. This guidelines is not about reducing conversation, but about moving toward a new approach, a re-purpose, a strategy, a project.

No “Giving a Paper”: If you suggest a session, you aren’t expected to “read” anything. Instead, your session should be a conversation that you facilitate. Give the group an idea, some shared “content” or questions, and let things unfold.

Push It To The Web: THATCamp Hybrid Pedagogy offers anyone on the web the ability to engage, share, and collaborate with us at Marylhurst University. Remember that others may be peeking in and consider ways to perforate the boundary of the room with a digital tool or two. Start with the GDoc link provided for the session on the schedule.

In this hack-a-thon, I suggest we design our own digital humanities undergraduate/graduate degree curriculum. There are many emerging programs that offer something like digital humanities (WSU’s Digital Technology and Culture and WSU-Vancouver’s Creative Media and Digital Culture, Marylhurst’s online/hybrid DH program, Georgia Tech’s Multimodal Communication program, FSU’s Histories of Text Technologies program, UCLA’s Digital Humanities program, U of Victoria’s DH program, N. Katherine Hayles’s call for Comparative Media Studies in her new book How We Think) that we can draw on. Some questions:

26 : 1

Teaching is a lonely profession. Let’s work on ways we can make it less solitary:

How can THATcampers play a role in bringing more of our faculty colleagues on board for practices of teaching and learning with social media?

How can THATcampers play a role in bringing more of our faculty colleagues on board for practices of teaching and learning with social media?

This question has lots of nuances and side issues that are not well represented in a straightforward statement of the topic. It’s not just social media, but all kinds of other emerging technologies and platforms for online learning. It’s not just conservative faculty, but often also digital native students who resist using social media to learn productively. Getting students to work socially breaks our existing models of assessment, and the technical tools that we need to properly do social assessment still need to be built. The list goes on.

But, if you are like me, you are predisposed to attend THATcamp because you have chosen the red pill, and believe that the new technologies are not just a optional layer on top of the social world of our colleagues and students. So I hope that this discussion session can provide an open-ended opportunity for like-minded teachers and scholars to share best practices for involving the whole faculty in the kind of higher education needed in the 21st century.

Lewis & Clark College has recently launched an initiative in digital field scholarship (DFS), spanning the humanities and sciences in an effort to explore how liberal education is enhanced via concepts of space/place, geolocated fieldwork, and associated devices/apps. Some examples I’m overseeing include an interdisciplinary undergraduate environmental research project, Situating the Global Environment, and a new DFS “sandbox” project for 2012–13 sponsored by NITLE and involving Lewis & Clark and three collaborating institutions.

In our limited HP ThatCamp time together, I’d like to propose a focus on DFS pedagogy (vs. e.g. technology). Here are a few starter questions:

Looking forward to meeting others!…

The Chronicle of Higher Education began a series last week titled “College, Reinvented“. In addition to 15 thought provoking articles suggesting how higher education should change (for instance “Grades Out, Badges In” and “Ditch the Monograph”), the series is also soliciting designs for new models. “If you could start your own institution of higher education from scratch, what would you build,” it asks. “Sketch out your idea—in prose or poetry, a picture, a video, or even a song—and send it to us.” Five will be published online, and one will be awarded $500. It’s the beginning of a populist think tank of sorts.

I love this idea. Since leaving the high school classroom in 2003, I have been imagining how school could work differently — how, in fact, it DOES work differently in many other areas of our lives (I explored this earlier this year at THATCamp SE with “Graded By The Street: Experiential Learning”). Institutions give us a wealth of stable structures (like windows, bathrooms, presidents, and libraries), but they also can present certain economic and pedagogical obstacles. In fact, Hybrid Pedagogy began after a series of conversations with Jesse about what our ideal school would look like.

The best THATCamps inspire work beyond their boundaries. I propose that we spend one session doing three things: 1) mapping the ideas already presented on “College, Reinvented,” 2) exploring the spaces that those pieces ignore, and 3) deciding what we (as individuals, as a large group, as teams) want to do to extend the reach of this inquiry beyond the contest (a blog, a report, an initiative?).

Oh, and we could also submit something(s). The deadline is Nov. 1. Submissions can include poems, videos, songs.

I’ll be the first to admit that I find Critical Code Studies intimidating. Yet, I find the questions posed by theorists in this field to be very productive for thinking about hybrid pedagogy across disciplines, and I think that approaching this topic in discussion may help us conceptualize our work. I will bring a few resources and pose some questions to get us started, and I look forward to hearing insights from those with more experience.

This article gives a solid, if strongly worded, overview of the topic. One of its main points, that “the implication for practice and research in digital media and learning is to begin to understand how coding, algorithms and software are involved in reconfiguring learning and the learner,” might be usefully revised into a discussion prompt: how are learning and the learner being reconfigured by digital infrastructure?

One of the things I find the most compelling about the digital humanities is its focus on building. Stephen Ramsay’s “On Building,” says that those involved in the digital humanities are fundamentally interested in making things – rather than exclusively focusing on the genre of criticism. I don’t believe, by the way, that criticism and building are (or have to be) mutually exclusive, but I do find his description of Alan Liu to be particularly interesting.

Being a man of great range, he [Liu] has gone on to do other very brilliant things (most significantly, in media studies), but I doubt very much if he’d be associated with DH at all had he not found his way to shop class with the rest of us bumbling hackers in the early nineties. He’s one of many crossover acts in DH, and those of us with less talent are surely more honored by the association. One of the reasons the DH community is so fond of Alan is because we feel like he gets it/us. He can talk all he wants about being a bricoleur, but we can see the grease under his fingernails. That is true of every “big name” I can think of in DH. Every single one.

The images of the craftsperson, the mechanic, and the carpenter circulate through my mind when I read this passage. As someone who teaches English, I want to make literature matter to students by showing them how it can be used to help them creatively think in other aspects of their lives. Those who do not go to graduate school, for example, may not particularly care about the intricacies of William Blake’s life (perish the thought!), but they may be inspired to integrate his visual imagery into their own creative work or take from his ideas.

Ultimately, I’d like to use this session to brainstorm a pedagogy of making in the humanities classroom. My interests are obviously focused on literary studies, since it is my discipline, but I’m also interested in broader questions of making in the humanities. What would a pedagogy of making look like? How can we distinguish it from (yet also draw inspiration from) creative writing courses, shop classes, and studio art classes? What rubrics and assignments can we create? How can we use content from humanities courses to teach the methodologies of making things in different modalities? And what are the limitations/possibilities for implementing larger curricular changes so that dissertations, theses, and other traditionally written academic performances could be rethought in terms of building?

In this general discussion session, we can consider the often-slippery definition of the digital humanities, especially as related to digital and hybrid pedagogies, and the ways in which teachers, scholars, and students identify as digital humanists.

People, and children in particular, learn best by doing, that is hands-on activities that reinforce and integrate knowledge. “Learning in place” (e.g. how to engineer bridges by visiting, discussing, climbing or building real bridges) has also been shown to greatly improve learning and make it long-lasting. So, how does one implement these kinds of learning in on-line courses/pedigogy? Thanks Jeri

We’ve been working on a portfolio framework here at Marylhurst, particularly in the context of our “Liberal Arts Core.” We just spent the last year on a series of conversations (accompanied by pie) on the ePortfolios&Pie Project. Our interest is in exactly what Sara is imagining – a process and practice that goes across courses (even outside the “garden wall” of the university) for students to connect and reflect on their learning. We’ve learned that, for a portfolio to support learning, we need to provide multiple opportunities for students to construct views in different contexts, for different audiences. We’ve also learned that we need to be ready to meet the student at their “points of reflection” – whether they are an entering student, a student entering a program/major, a student stopping midpoint to evaluate their progress toward their goals, the student ready to graduate, or the student at any point in their learning that they choose. And, we faculty need to engage students directly around reflection, in order for the portfolio framework to have value. I wonder if we could do a couple of working sessions, toward a project we might complete? For example, we might create several personas (different, fully imagined people, with names and everything), and walk through what a portfolio framework might mean to them.

Questions that I’m interested in exploring:

What is the purpose of reflection? When does reflection occur (e.g. every class?) and on what (e.g. individual artifact such as a paper and/or or on a “whole” that is emerging for the student)? How can we make continuous engagement (reflection and connection) meaningful for students?

How does the “magic” happen? How do we turn what is otherwise just a collection of artifacts (papers, etc.) into a meaningful, rich & deep learning experience for students? What does that mean about reflective practice (our own as learners, the university as a community of learners)?

How can we use ePortfolios to give students both the private, safe space to try & fail, to be authentic selves and the public showcase space that summarizes their learning at a particular moment in time? Is it necessary for the safe space to be private? Will a public space curb students’ willingness to take risks and be authentic?

As an ed-tech librarian I’ve been working with different departments on creating an online portfolio piece for their students. Unfortunately, this has been limited so far to portfolios that only demonstrate a student’s work in a specific department or class – not the student’s work across all classes, activities, and experiences.

I would really love to hear from other campers about their exposure to student portfolios or any method that went after a holistic assessment of the student rather than just a single class assessment. It seems like we are training our students to see their time in college as unrelated little sound bites from class to class rather than seeing the big picture of their overall education.

In my dream world, having this big picture approach would mean students could create projects that span across their classes, including elements from Biology, History, and Literature, for example. Faculty would get a sense of what their colleagues were doing in other classes because they would see it in their own students’ work. But I will also be the first to admit that I can be naive about these things, so another part of this discussion might be how such an interdisciplinary approach to student assessment would or would not work.

In the last #digped conversation, I cited Cheryl Ball’s paper “Show, Not Tell” explaining “Most people have not been trained to view online forums as scholarly. We are encouraged to read and write, in any and every way, but ‘new media scholarship may be dismissed as having an unnecessarily fussy ‘advertising aesthetic’… making it unworthy as a scholarly text in the eyes of the reader.’” After spending time with Ball’s article for a Computers and Composition course I’m taking here at Georgia State University, I then spent some time writing a critique for a paper called “After Digital Storytelling: Video Composing in the New Media Age” by Megan Fulwiler and Kim Middleton. This article came out earlier this year and opens up a very interesting, and very relevant discussion about digital media production. It asks the question, “when we ask out students to produce multimodal compositions, what is it that we are asking them to do?” For many of us, this question directly translates to another: “How do I evaluate a product that deals in multimodality?” If a students creates something flashy or high in aesthetic quality, how do we begin to critique, or evaluate this?

I propose a session in which we discuss the questions above. Multimodal texts, such as video production, blog posting, or even slide shows are present in all courses we teach and it is crucial that we are clear in what we ask for from students. So I ask another question: “If we know what we are asking for, do we then know what to evaluate?” And another (they just keep coming) “what do we do with the unexpected?”

This is inspired by a similar session I saw at THATcamp LAC 2011. Anyone who wanted to share a cool tool / app / method that they were using in their classes or personal workflow could use the classroom computer to quickly demo the tool / app / method in about 3 minutes. We were able to see over a dozen different new things or new ideas applied to old things in a very short amount of time. It worked out great as an after-lunch pick-me-up kind of session and generated lots of questions, sharing, and quick experimenting.

Now that the face-to-face classroom is no longer the de facto setting for learning, what are the best practices for blending embodiment and virtuality?

I work in and study virtual classroom software in the context of my classes at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg School of Communication. Living in Portland, OR but working in Los Angeles, I convene class virtually & synchronously 3 weeks each month; I commute to L.A. one week monthly, run class face-to-face, and meet with each of my students individually.

We study interfaces in addition our course content, social media. I have also taught a Networked Culture seminar at Washington State Vancouver’s Creative Media and Digital Culture program, where students met virtually three times over the course of the semester.

My students use authoring software to make artifacts for our real-world social media campaigns and study relevant contexts such as fair use, transmedia storytelling, “playbor” (digital labor + play), mobility + ubiquitous computing, and hybrid collaboration.

Teaching seminars virtually has caused me to notice how much I blend my senses in the face-to-face classroom. I rely on hearing and proprioception much more than I would have guessed. Both of those modes are significantly limited in virtual classroom software.

After our first day in the virtual classroom, one of my students said, “[virtual classroom software] is so easy. I’m more accustomed to looking at a screen than a professor. It scares me that this is what the classroom is going to become.”

Why do you think she said that?

Proposed subjects — please add yours: